Introduction

This article is an advanced-level technical elaboration of how Orleans can migrate grains. Note this is not about rebalancing nor repartitioning, rather about how the actual process of moving an activation from one silo to another, while transferring state and queued up request, at the same time ensuring the final result does not end up having duplicate activations in the cluster.

Primer Grain

Let's take this simple grain as an example. There are two ways how one can instruct Orleans to migrate it.

- Externally - Via casting to

IGrainManagementExtensionand callingMigrateOnIdleon the returned reference. - Internally - Via directly calling

MigrateOnIdle, if we are within a grain context.

var grainFactory = host.Services.GetRequiredService<IGrainFactory>();

var grain = grainFactory.GetGrain<IMyGrain>("123");

var siloAddress = ...; // 10.0.0.2

RequestContext.Set(IPlacementDirector.PlacementHintKey, siloAddress);

// Migrate Externally

await grain.Cast<IGrainManagementExtension>().MigrateOnIdle();

public interface IMyGrain : IGrainWithStringKey

{

Task Ping();

}

public class MyGrain : Grain, IMyGrain

{

public Task Ping()

{

Console.WriteLine("Pong");

RequestContext.Set(

IPlacementDirector.PlacementHintKey, siloAddress);

// Migrate Internally

MigrateOnIdle();

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}In order for the internal case to work, one does not necessarily need to inhert from the base Grain class, but the code needs to be within a grain context! Failing to do so will throw an InvalidOperationException. This is done to prevent migration (and other) operations from being attempted on grains that lack access to essential runtime services. Having said that, the following is just as valid as the above:

// Note: No inheritance to base Grain class!

public class MyPocoGrain : IGrainBase, IMyGrain

{

public IGrainContext GrainContext { get; }

public MyPocoGrain(IGrainContext context)

{

GrainContext = context;

}

public Task Ping()

{

Console.WriteLine("Pong");

RequestContext.Set(

IPlacementDirector.PlacementHintKey, siloAddress);

// Migrate Internally

this.MigrateOnIdle();

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}The above ways would fall into what I would call "user" migrations, so migrations initiated from the users' code. Orleans does perform migrations also automatically (if enabled),

via the Activation Rebalancer (MAR) & Activation Repartitioner (LAR).

Process Overview

Grain migration in Orleans follows these high-level steps:

- Initiation - Migration is triggered via

Migrate/MigrateOnIdle. - Placement - A new location is selected using the placement service.

- Deactivation - The grain begins deactivating with a migration context.

- Dehydration - State is captured into a

MigrationContext/DehydrationContext.- Participation - Migration participants are notified about the dehydration.

- Transfer - The migration context is sent to the target silo.

- Rehydration - A new activation is created and state is restored.

- Participation - Migration participants are notified about the rehydration.

- Directory Update - The grain directory is atomically updated.

Process Details

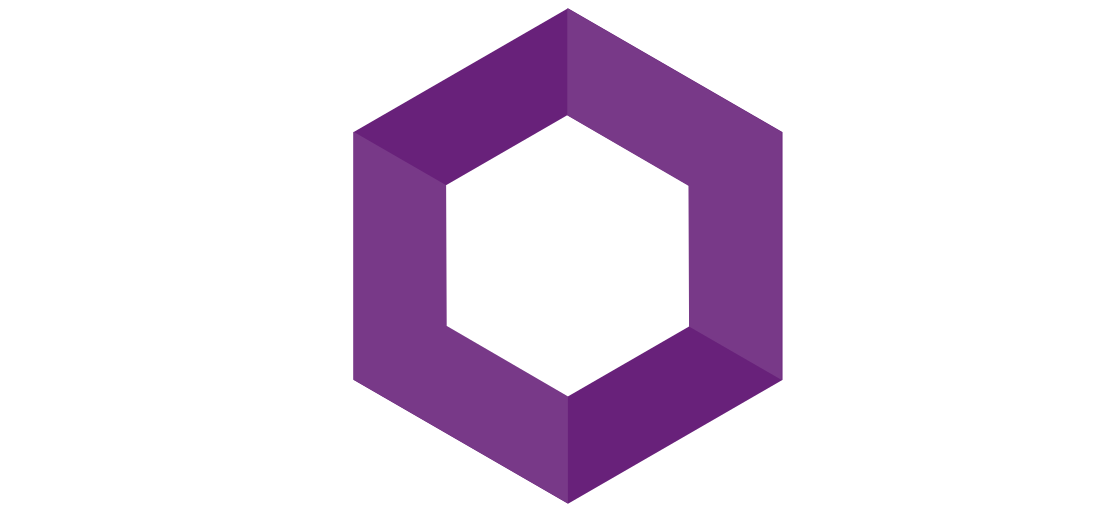

Regardless where the source of migration comes from, they all rely on the same underlying process/mechanism. It all begins with a call to either MigrateOnIdle (from user code), or directly into the ActivationData's Migrate (from MAR & LAR).

The reason why MAR & LAR call Migrate directly is because they are components that know exactly where to migrate the grain to. Whereas with user code, Orleans can not know for sure that the user did hint to the runtime where they want the grain to migrate to.

This is an important distinction because if you as a user do not hint Orleans where to migrate the grain, Orleans simply will "no-op" your migration request as part of the MigrateOnIdle process is to run placement, and that will result in the current silo being the target, which means no migration will take place. But, we assume that you do hint to Orleans a different (compatible) silo as the traget of migration, so placement will run and pick the target silo as the host of the new activation.

Migration is a rather delicate process, and Orleans knows that requests may hit the current activation at any point during this phase transition. The grain must be able to handle those requests, so the first thing that happens is that the grain will set its ForwardingAddress equal to the target silo's address, essentially making itself act as router.

Next, if the grain is not deactivating, the request context (which can carry over in-memory state) is captured into a migration context (which will transfer that state). Doing this signals to the deactivation process that a migration is occurring. This part is very important because in order for the grain to migrate, it needs to perform the deactivation process first. The grain will schedule its own deactivation by means of enqueuing a deactivation command into its internal operations queue.

With that, the process is finished, at least from the prespective of user-code/MAR/LAR. This just marks the begining though!

Even though the process looks synchronous, it is actually asynchronous or rather event-driven. With the deactivation having been enqueued, the grain's work loop will get woken up, and the deactivation process will continue in the background.

Remember how I mentioned that we set the migration context i.e. DehydrationContext field, before enqueuing the deactivation command! The deactivation process checks if its not null (it wont be), next it checks if the ForwardingAddress has been set, if its not, then placement will run.

Although I mentioned that we do set the ForwardingAddress to the target silo's address, it can also not be set at this point in the process, given migration has been initiated internally from MAR/LAR. In the case of it being initiated externally through user-code, it will be set at this point.

Whether it is the former or later, the ForwardingAddress will be set at some point, and the grain will begin the dehydration process, which means that all (optional) migration participants will get invoked, and the dehydration context will be passed to each of them. The idea here is that participants can attach in-memory state to the context that they want to get preserved when the grain reactivates on the target silo.

Participation Detour

Anything can be a migration participant so long as it implements the IGrainMigrationParticipant interface. The grain can participate on its own given it wants to preserve its in-memory state.

public class MyPocoGrain : IGrainBase, IMyGrain, IGrainMigrationParticipant

{

private int _counter;

public IGrainContext GrainContext { get; }

public MyPocoGrain(IGrainContext context)

{

GrainContext = context;

}

public void OnDehydrate(IDehydrationContext dehydrationContext)

{

dehydrationContext.TryAddValue("counter-key", _counter);

}

public void OnRehydrate(IRehydrationContext rehydrationContext)

{

if (rehydrationContext.TryGetValue<int>(

"counter-key", out var value))

{

_counter = value;

}

}

public Task Ping()

{

_counter++;

Console.WriteLine("Pong");

this.MigrateOnIdle();

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}Above we can see how the migrating grain itself becomes a participant. Though as mentioned, anything can become a participant: grains, storage providers, even arbitrary types. The neat thing about grains' is that they just have to implement the interface, but for other components the grain must be told to register the participant. Below we can see how the grain registeres the type Counter as a migration participant into its lifecycle.

public class MyPocoGrain : IGrainBase, IMyGrain

{

private Counter _counter = new();

public IGrainContext GrainContext { get; }

public MyPocoGrain(IGrainContext context)

{

GrainContext = context;

GrainContext.ObservableLifecycle.AddMigrationParticipant(_counter);

}

public Task Ping()

{

_counter.Inc();

Console.WriteLine("Pong");

this.MigrateOnIdle();

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

private class Counter : IGrainMigrationParticipant

{

public int Value { get; private set; }

public void Inc() => Value++;

void IGrainMigrationParticipant.OnDehydrate(

IDehydrationContext dehydrationContext)

{

dehydrationContext.TryAddValue("counter-key", Value);

}

void IGrainMigrationParticipant.OnRehydrate(

IRehydrationContext rehydrationContext)

{

if (rehydrationContext.TryGetValue<int>(

"counter-key", out var value))

{

Value = value;

}

}

}

}Anyhow, going back to the migration process. The ForwardingAddress has been set, so any further requests to this activation will forward to the new address. The participants may have attached extra state to the DehydrationContext, and one more thing the grain does, is it attaches one extra bit of information which is its GrainAddress, as we shall see later on this will be a very important piece to ensure that the cluster does not end up having two activations of the same type (sharing the key of course).

The MigrationContext along with the GrainId and the ForwardingAddress is sent over to the local migration manager, and the grain asks it to perform the migration to the target silo. It is the manager who takes over from now and it returns a ValueTask which represents the migration promise, which in turn the migrating activation will await it.

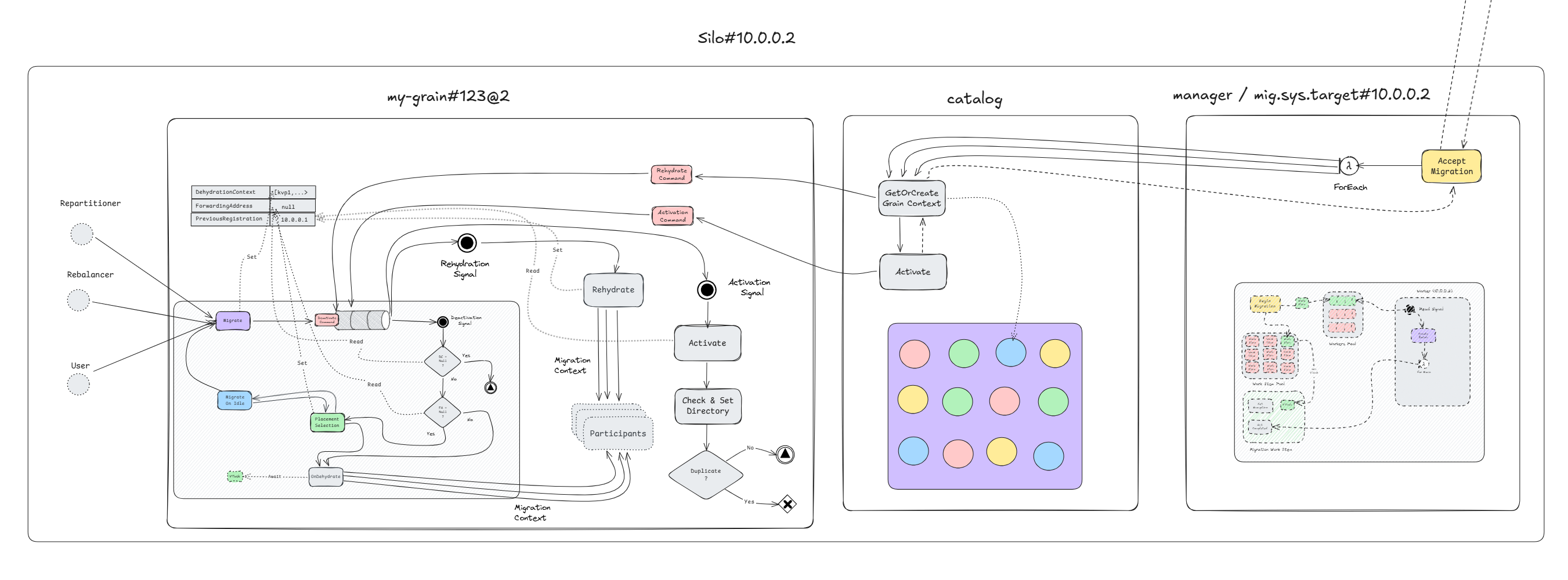

So far what I have written can be described by the following diagram.

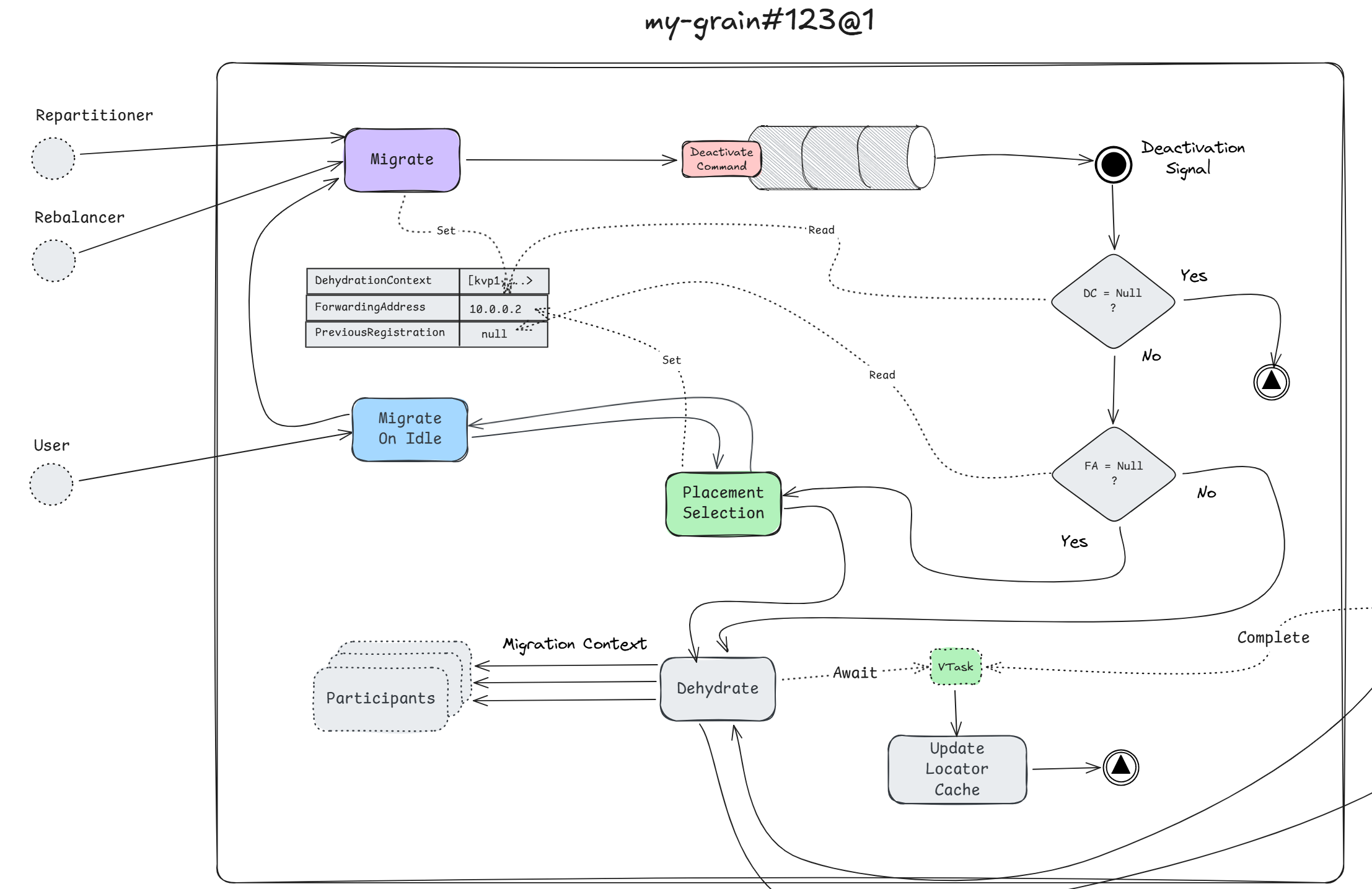

Migration Manager

Every silo has a so called migration manager. The manager is actually two components in one.

- A service that migrating activations talk to.

- A system target that its peers talk to.

Donor Manager

The part which activations interface with, is the "service" part, and that is the one that accepts the migration request. Since there is one manager per silo, naturally this represents a hot-path, and it is treated very carefully. Efficiency is crucial here, but also non-blocking behavior. Each manager keeps a pool of so called MigrationWorkItem's.

MigrationWorkItem implements IValueTaskSource in order to provide a lightweight, poolable, async operation, which represents the migration promise. This way, the manager avoids a lot of Task allocation overhead while enabling the async/await pattern. The manager does not create a MigrationWorkItem for each migration request, instead it dedicates one by pooling the once that are reset and ready to be consumed, and uses them to track the asynchronous migration of grain activations between silos. Of course, if no work items are available or simply not in a state to be consumed, it will create one on-demand.

Because these are poolable async operations, the ValueTask that they expose is the one that is handed over to the migrating activation (the one awaiting the result). For each silo in the cluster, the manager creates a System.Threading.Channel for the work items to be passed on. For each migration request, it pumps the work items to the respective channel, which in turn another work loop awaits on.

This way the manager can quickly acknowledge that it accepted the migration request, and hands over the ValueTask. The work loop reads it from the respective channel, and prepares a migration batch to send it over to its peer on the target silo. It should be obvious why the managers batch migration requests, because each call is a network call to another silo, otherwise there would not be any migration, right?

At this point the manager is awaiting the response from the peer manager on the target silo, and the migrating activation is awaiting the ValueTask exposed by the MigrationWorkItem. From the storyline, the current manager = mig.sys.target#10.0.0.1 is the donor, and the target manager = mig.sys.target#10.0.0.2 is the acceptor.

But both can be donors & acceptors!

When the acceptor has accepted the migration batch, the donor proceeds to "complete" the respective MigrationWorkItem, which just resets the underlying ManualResetValueTaskSourceCore which in turn unblocks the awaiter (which is the migrating activation). The reseting also returns the MigrationWorkItem to the pool so it can be reused for future migration requests. If any exception is thrown while the donor is awaiting the acceptor, than the whole batch is treated as a failure. The same exception is propagated to all migrating activations for the current batch. The work items are neverthelese returned to the pool, and can be reused later.

Assuming that all went fine, the migrating activation gets notified via standard async/await semantics (since its awaiting the ValueTask), and proceeds to update the locator cache. Note that the migrating activation = my-grain#123@1 does not unregister itself from the grain directory! Instead it is the migrated activation = my-grain#123@2 which performs a so called "check-and-set", which is an atomic replacement operation on the directory.

This is to ensure a correct hand-off, and prevent a window where the grain has no valid registration. We will talk about this in more detail later on, but if there was an exception during the migration, and since the migrating activation already is deep down in the deactivation process, it knows that there can not be another activation besides itself, so it has to unregister itself from the grain directory. If another request (not migration, but a message) comes along, the contacted silo (which likely will be the current one) will re-activate and register a new incarnation of the grain.

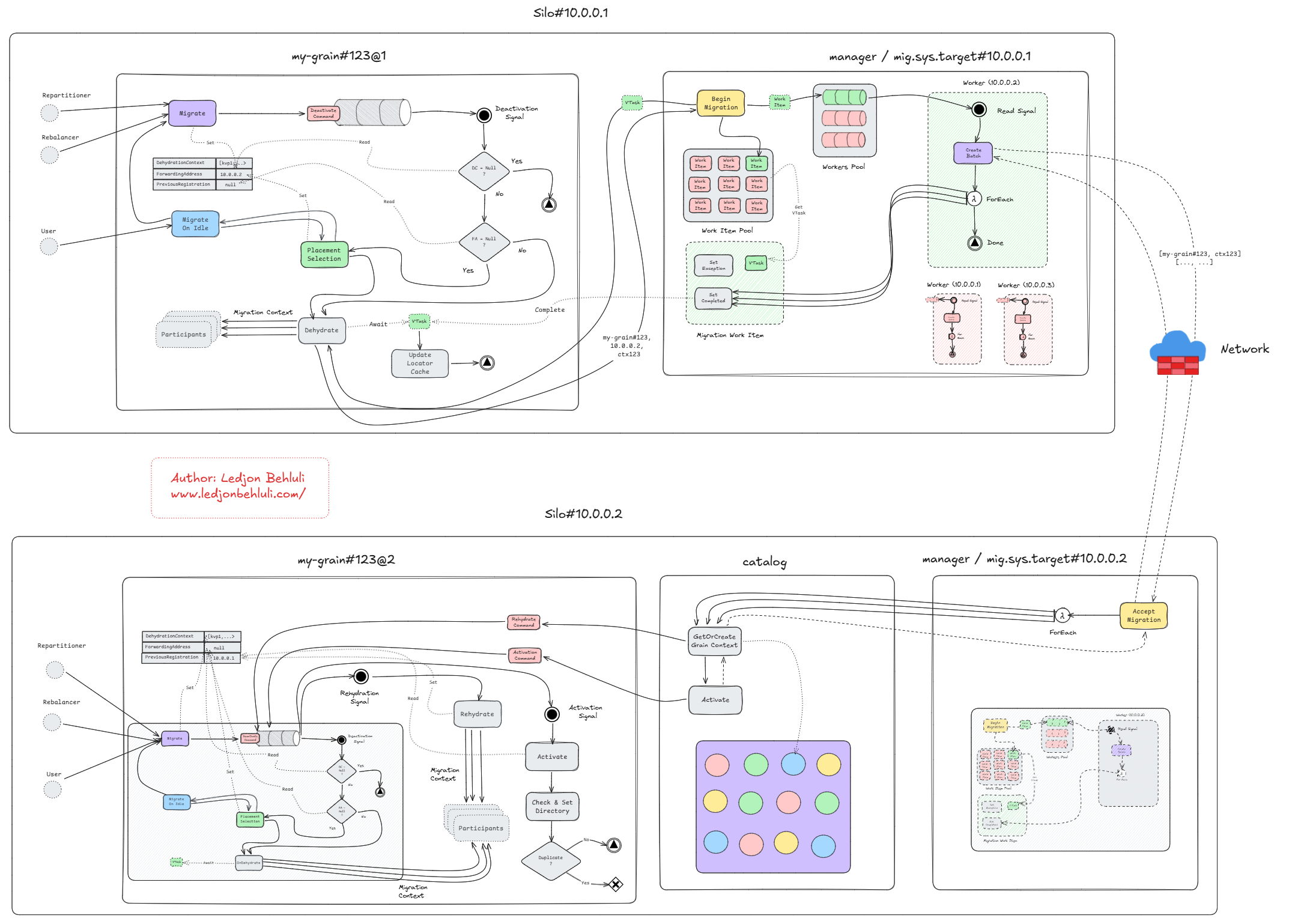

This can be described by the following diagram.

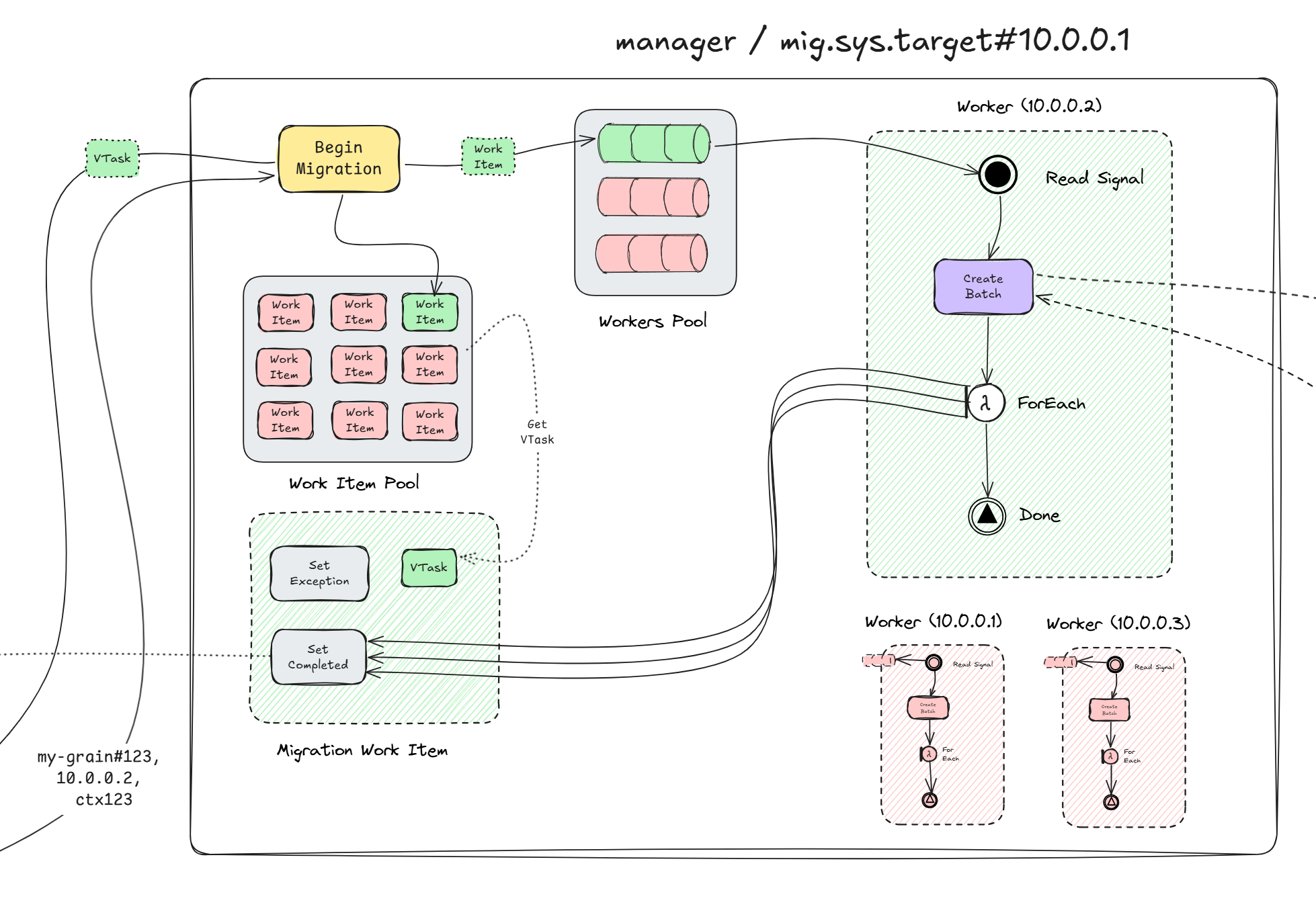

Or as a bigger picture of the activation and the local manager working together.

Acceptor Manager

As mentioned there is one migration manager per silo, so naturally the target silo = 10.0.0.2 will have one manager too namely = mig.sys.target#10.0.0.2, this is the acceptor manager.

As the name implies, the acceptor will accept the migration batch, and for every package it will consult the grain catalog to either get or create the activation. Of course the activation does not yet exist in the target silo, so the creation path is taken from the catalog. The grain activator will first create the grain context, and will begin the rehydration process.

Similarly how deactivation was triggered asynchronously via the signaling constructs, so is rehydration! The batch can contain up to 1,000 migrations, and the mananger should not have to wait for all of them to finish migration. Therefor rehydration is scheduled via a command, which in turn is followed by an activation command scheduling.

Part of the rehydration process is the retrival of the GrainAddress from the MigrationContext, recall that I mentioned before.

The grain attaches one extra bit of information which is its

GrainAddress...

It is now that this piece of information comes into play. The new activation = my-grain#123@2 takes that GrainAddress from the context, and sets its local PreviousRegistration value to that address. Then it proceeds to call OnRehydrate on all migration participants, which essentially means it tells them "hey, I am going live and I migrated, please restore your/mine state".

As mentioned before, storage providers can also be participants, and by default the bridge that connects a grains' storage to any provider, is itself a participant, that is how Orleans automatically can migrate the grains' persisted state, but user-requested, in-memory state gets migrated the same way it just requires some manual work from the developer.

Once rehydration finishes, the scheduled activation command begins. A lot happens there, but for the migration process the important bit is that this migrated activation will now register itself in the grain directory.

This activation will perform the "check-and-set" operation on the directoy. The "check-and-set", or more formally known as compare-and-swap operation is an optimistic concurrency control mechanism in the directory that allows conditional registration of an activation, only if the current directory view of an activation, matches an expected previous one.

The key parameter that determines that is the PreviousRegistration, which essentially is the GrainAddress of the migrating grain. Note that the GrainAddress embeds the SiloAddress, so it will be different from the current silo's address.

As the name implies, "check-and-set" has a "check" and a "set" part.

- Check - If there is an existing activation AND it does not match the

PreviousAddressparameter, the operation fails and returns the existing address. - Set - If the check passes, so no existing activation OR an existing activation which matches the

PreviousAddressparameter, the new activation is registered.

This prevents dual-activations, because the migrating activation does not unregister from the directory, it is the migrated activation who registers using check-and-set with the migrating activation's address as the PreviousAddress. If migration succeeds, the target replaces the source atomically. If migration fails, and both try to register independently, only one succeeds (the other gets ForwardingAddress and deactivates)

Note that the rehydration, activation, and registration for each activation is happening asynchronously, and the acceptor manager has already returned the response to the donor migrator. In case the migrating activation has received requests, it has its ForwardingAddress set to the new activation's silo address, so all user-messages are being forwarded to the target silo, and queued up until the new activation has fully activated. Whenever the new activation is fully activated it will immediately start to address those messages.

Everything on the target silo can be described by the following diagram.

Or as a bigger picture of the whole migration process, across both silos. Click here to enlarge!

If you found this article helpful please give it a share in your favorite forums 😉.